Rambling again. Brain is going in all directions. Need order (at least, the idea of it). Art is a release, as explained in previous post. Need that passion back. Personal hangups aside, I think its high time I began talking about creative people again, don't you think, Void? For a primer to my upcoming articles, I will be putting Peter Chung in the spotlight. The man behind the 90's unorthodox animated series Aeon Flux.

The topic for the day is: film and comics - are they a good match? This article was written by Mr. Chung, and was written way, waaay back in 1998! But a recent interview with Mr. Chung stated that he really had nothing to change in that article he wrote - which means the industry is still facing the problems it did almost a decade ago.

How does one justify the activity of making comics, or, for that matter, movies? What could be more frivolous, a worse influence on today's youth, and a greater erosion on the public's literacy and grasp of higher cultural values? However there is nothing inherently less serious or respectable about visual narrative media as compared to traditional literature -- only in the debased way that the majority of comics artists and filmmakers use them. In fact, the best visual narratives push the audience to levels of interpretation so new and so complex, that they aren't even recognized by the public. This is the source of the power of popular media; they affect the audience subconsciously. Even so, the lack of visual literacy in the general public is suffocating the progress of both comics and film as serious artistic tools.

As a writer and director of animated films, I've often been inspired and influenced by the great comic book artists. But even while I take in their pleasures with quiet gratitude, I've always felt that the very qualities which enthrall me are probably too elusive, too rarefied, to ever be appreciated by the mainstream public. For me, it is that deeply personal sense of discovering something hidden, something which might be missed by too casual a glance, that is the reward offered by art in any medium. Yet the current atmosphere of commercialized production of visual media, works against this from happening.

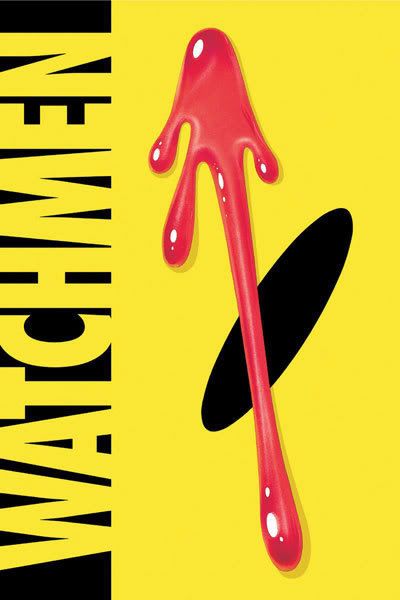

I've only read Alan Moore's Watchmen so far, because I never

I've only read Alan Moore's Watchmen so far, because I neverreally cared so much about comics (until now) and it's the kind of book

you have to read multiple times to get all the ideas the author was trying

to convey. Each panel is a story within itself. I kind of touched upon this in

my post on Multi-layered Narratives

We may regard comics as a rudimentary type of film, lacking movement and sound. Looking at the problems with comics lets us study the basic nature of visual narrative and eventually reach a better understanding of the importance of film.

Comics And Hollywood: An Unhappy Marriage

The dismal state of comics in the U.S., both as an industry and as an art form, gives little hope that it can break through as a medium with an influence beyond the closed subculture it now occupies. I rarely pick up comics any more. I'd rather watch an old movie on video to satisfy my retinal needs. As for reading, I prefer an actual book than to suffer trying to decipher the incoherent page layouts of today's comics.

Ironically, the wide dissemination of comics-derived films and TV. programs can be blamed for the decline in both the level of public interest in comics, and in the quality of the output of comics creators. That is, the success that comics enjoy by their acceptance in the more mainstream media of film and TV. is the very thing which is suppressing their artistic evolution.

When Hollywood adapts comic characters to the big screen, there is an emasculation effect whereby producers and directors, refusing to acknowledge serious themes present in the original work, exploit only the "high-recognition/high concept" aspects for their own commercial ends. Comics are regarded as trafficking in stereotypes, and thus, as a source, provide an easy excuse for directors unequipped or unwilling to handle complex characterization. Mainstream audiences, seeing only the bastardized movie version of a comics character, have their preconceptions confirmed, thus inhibiting their desire to consider picking up a comic book to read.

In fairness, 2001's Spiderman did open comics to Hollywood. The series

In fairness, 2001's Spiderman did open comics to Hollywood. The series

did well enough to warrant plenty of sequels (2 being a lot already)

Comic soon: Ironman! (At the time of this writing)

Also forgot to mention the Watchmen film adaptation. You won't

find Alan Moore anywhere in the theatres when that finally

happens. Honestly, it can't be done without dumbing a lot of

things down, unless a really great director is at the helm.

Comics creators are only too eager to perpetuate this cycle by offering characters tailored with an obvious eye toward movie deals and merchandising licenses. These characters can be recognized by their flashier costumes, bigger muscles, bigger breasts, wider array of props, weapons, and vehicles, and most importantly, their pre-stripped down personalities (mostly consisting of a single facial expression), ready for easy portrayal by untalented athletes/models. Hardly a comic book character appears today without this aim in mind, and the trend is effectively dumbing down the readership.

Text ss. Image: The Unresolved Problem

There is very little care or interest on the part of today's comics artists in the craft of storytelling. The readers are not demanding (those who are have long left the store), therefore the artists feel no need to learn the brass tacks of visual continuity. The truth is that making a good comic book is a lot harder than most artists realize. (Knowing the difficulty has kept me from entering the field, in spite of occasional requests by editors for me to join in. Mostly, I'm dissuaded by witnessing the poor public response to artistically worthy comics.)

Recent American comics seem to fall into two camps:

1. The writer-oriented type, characterized by a narrative laden with running commentary (often the interior monologue of the main character) which makes the drawings seem gratuitous-- in fact, a hindrance to smooth reading, since the text seems complete without them-- and which makes me wonder why I don't just read a real book instead. To me, this style is antithetical to the nature of visual narrative. A comics writer who relies heavily on self-analyzing his own story as he tells it: a. doesn't trust the reader to get the point; and b. hasn't figured out how to stage events so that their meaning is revealed through clues of behavior, rather than direct pronouncements of a character's thoughts.

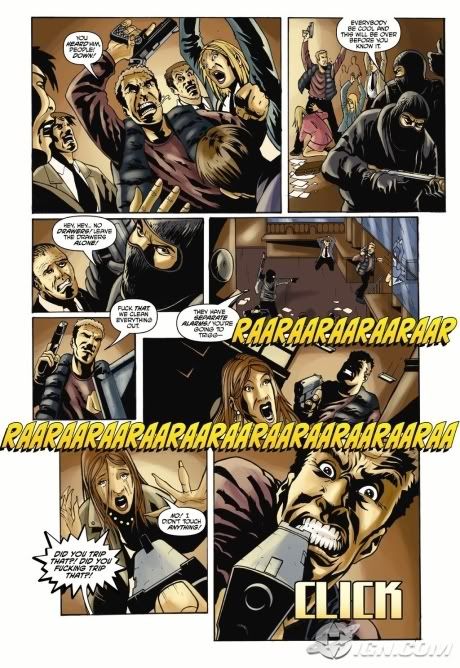

2. The artist-oriented type, characterized by nonstop action/glamour posing, a fetishistic emphasis on anatomy, unclear geography (due to the near absence of backgrounds), confusing chronology (due to the total absence of pacing), and the sense in the reader that the pages have been contrived to allow the artist to draw only what he enjoys drawing and leaving out what he does not, regardless of its function in the story being told. Many young artists aspire to work in comics because they enjoy drawing the human figure. Typically, they collect comics to study and copy the techniques of their favorite artists. The mastery of illustration technique is laborious in itself and they have no time or inclination to read the stories in the comics they buy. Then they eventually become working professionals, drawing comics which are bought only for their flashy artwork.

Sin City had a lot of narration between scenes, proving why these kind of overbearing narratives don't really work. However, if you liked Sin City, then good for you. I actually liked it myself, but this flaw results in redudancy in the way the story was told...

Sin City had a lot of narration between scenes, proving why these kind of overbearing narratives don't really work. However, if you liked Sin City, then good for you. I actually liked it myself, but this flaw results in redudancy in the way the story was told...

What is rare to find is a work marked by the good integration of art and story; of form and content. I've found through working alongside comic book artists, that they have little awareness of the principles of film grammar. While I believe that the comics medium is more forgiving than film in the allowance for "cheated" continuity, I have no doubt that the legibility, and thus accessibility, of comics by a mainstream public would be improved greatly by the application of filmic language.

In order to approach a critical method of judging comics' value as visual narrative, we must first decide where they belong in the scale between visual media and literature. Because they are printed on paper, we refer to them in literary terms-- comic book; graphic novel. In practice, the fact that comics stories convey scenes through images rather than through description, make them work on the reader more like film. Still, I wouldn't insist that comics be judged according to the criteria we use on film, since no one seems to agree on what those are either.

Literature vs. Film

People often repeat the fallacy that "film is a passive medium". The statement is usually elaborated like this: "When I read a story in a book, I have to use my imagination to conjure up what the characters look like, the sound of their voices, the appearance of their surroundings, the house, the landscape. When I see a movie, those things are all nailed down for me, so I don't feel as involved." What the person is describing are the most obvious aspects of a given story, that is, its physical properties. They are, in fact, the least interesting and least important components of a story. I do not read books in order to imagine the physical appearance of things.

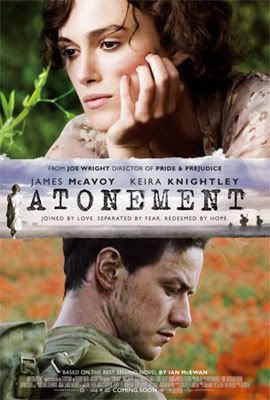

This is a great book, but does it translate well as a movie?

This is a great book, but does it translate well as a movie?

It's conundrums like this that has plagued the industry for decades.

Conversely, there are things which are typically spelled out in a book, but which must be imagined in a film. These are the intangibles, the important stuff; what are the characters thinking and feeling? Novelists have the advantage of being very explicit about the internal experience, and they indulge it, often to the detriment of the reader's power to infer. Good writers are the ones who maneuver around this pitfall. A book's ability to describe thoughts and feelings is a liability, not an advantage, if used to declaim its themes rather than evoke the desired consciousness in the reader.

Unfortunately, in practice, a great many mainstream filmmakers regard it as their job to inhibit interpretation by the viewer. No doubt, this is due to the increasing commercial pressures of the movie industry. Coming out of the theater after a thought-provoking film, I've heard viewers comment, "I was confused because I didn't know who I was supposed to be rooting for." Doesn't it occur to them that maybe that decision was being left up to them? That the exercise of our interpretive faculties is what makes our minds free? These people are usually the same ones who complain that movies don't let them use their imaginations.

In a review of Aeon Flux in the L.A. Times, the reviewer remarked that the director (me) wasn't doing his job in defining who in the story was good and who was bad, and thereby accused said director (me) of being "lazy". The presumptuousness of such an attitude would make me laugh, if only it weren't so prevalent.

A good film is one that requires the viewer to create, through an orchestration of impressions, the meaning of its events. It is, in the end, our ability to create meaning out of the raw experience of life that makes us human. It is the exercise of our faculty to discover meaning which is the purpose of art. The didactic imparting of moral or political messages is emphatically not the purpose of art-- that is what we call propaganda.

The inevitable challenge for anyone working in narrative film or comics is how to convey the internal states of the characters. Understanding this issue is the key to discerning visual versus literary storytelling. Resorting to the use of voice-over narration or thought balloons is a literary solution that undermines the power of images (the exception is in cases where narration is used ironically in counterpoint to what is being shown, e.g. A Clockwork Orange). For certain subjects, strict realism, where the mental realm of others is impenetrable, can be effective (e.g. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer). However, I would find it depressingly limiting as a filmmaker to be restricted to physical reality to express the world of ideas. Realism has the effect of granting primary status to the external, whereas in our experience, the internal is often the more important. The great filmmakers understand this trap -- that strict "realism" is, in fact, the least true interpretation of our experience of life; that a work springing from the imagination which adopts the guise of objective reality can only be a lie.

Comics And Hollywood: An Unhappy Marriage

The dismal state of comics in the U.S., both as an industry and as an art form, gives little hope that it can break through as a medium with an influence beyond the closed subculture it now occupies. I rarely pick up comics any more. I'd rather watch an old movie on video to satisfy my retinal needs. As for reading, I prefer an actual book than to suffer trying to decipher the incoherent page layouts of today's comics.

Ironically, the wide dissemination of comics-derived films and TV. programs can be blamed for the decline in both the level of public interest in comics, and in the quality of the output of comics creators. That is, the success that comics enjoy by their acceptance in the more mainstream media of film and TV. is the very thing which is suppressing their artistic evolution.

When Hollywood adapts comic characters to the big screen, there is an emasculation effect whereby producers and directors, refusing to acknowledge serious themes present in the original work, exploit only the "high-recognition/high concept" aspects for their own commercial ends. Comics are regarded as trafficking in stereotypes, and thus, as a source, provide an easy excuse for directors unequipped or unwilling to handle complex characterization. Mainstream audiences, seeing only the bastardized movie version of a comics character, have their preconceptions confirmed, thus inhibiting their desire to consider picking up a comic book to read.

In fairness, 2001's Spiderman did open comics to Hollywood. The series

In fairness, 2001's Spiderman did open comics to Hollywood. The seriesdid well enough to warrant plenty of sequels (2 being a lot already)

Comic soon: Ironman! (At the time of this writing)

Also forgot to mention the Watchmen film adaptation. You won't

find Alan Moore anywhere in the theatres when that finally

happens. Honestly, it can't be done without dumbing a lot of

things down, unless a really great director is at the helm.

Comics creators are only too eager to perpetuate this cycle by offering characters tailored with an obvious eye toward movie deals and merchandising licenses. These characters can be recognized by their flashier costumes, bigger muscles, bigger breasts, wider array of props, weapons, and vehicles, and most importantly, their pre-stripped down personalities (mostly consisting of a single facial expression), ready for easy portrayal by untalented athletes/models. Hardly a comic book character appears today without this aim in mind, and the trend is effectively dumbing down the readership.

Text ss. Image: The Unresolved Problem

There is very little care or interest on the part of today's comics artists in the craft of storytelling. The readers are not demanding (those who are have long left the store), therefore the artists feel no need to learn the brass tacks of visual continuity. The truth is that making a good comic book is a lot harder than most artists realize. (Knowing the difficulty has kept me from entering the field, in spite of occasional requests by editors for me to join in. Mostly, I'm dissuaded by witnessing the poor public response to artistically worthy comics.)

Recent American comics seem to fall into two camps:

1. The writer-oriented type, characterized by a narrative laden with running commentary (often the interior monologue of the main character) which makes the drawings seem gratuitous-- in fact, a hindrance to smooth reading, since the text seems complete without them-- and which makes me wonder why I don't just read a real book instead. To me, this style is antithetical to the nature of visual narrative. A comics writer who relies heavily on self-analyzing his own story as he tells it: a. doesn't trust the reader to get the point; and b. hasn't figured out how to stage events so that their meaning is revealed through clues of behavior, rather than direct pronouncements of a character's thoughts.

2. The artist-oriented type, characterized by nonstop action/glamour posing, a fetishistic emphasis on anatomy, unclear geography (due to the near absence of backgrounds), confusing chronology (due to the total absence of pacing), and the sense in the reader that the pages have been contrived to allow the artist to draw only what he enjoys drawing and leaving out what he does not, regardless of its function in the story being told. Many young artists aspire to work in comics because they enjoy drawing the human figure. Typically, they collect comics to study and copy the techniques of their favorite artists. The mastery of illustration technique is laborious in itself and they have no time or inclination to read the stories in the comics they buy. Then they eventually become working professionals, drawing comics which are bought only for their flashy artwork.

Comics Aren't Literature

Sin City had a lot of narration between scenes, proving why these kind of overbearing narratives don't really work. However, if you liked Sin City, then good for you. I actually liked it myself, but this flaw results in redudancy in the way the story was told...

Sin City had a lot of narration between scenes, proving why these kind of overbearing narratives don't really work. However, if you liked Sin City, then good for you. I actually liked it myself, but this flaw results in redudancy in the way the story was told... What is rare to find is a work marked by the good integration of art and story; of form and content. I've found through working alongside comic book artists, that they have little awareness of the principles of film grammar. While I believe that the comics medium is more forgiving than film in the allowance for "cheated" continuity, I have no doubt that the legibility, and thus accessibility, of comics by a mainstream public would be improved greatly by the application of filmic language.

In order to approach a critical method of judging comics' value as visual narrative, we must first decide where they belong in the scale between visual media and literature. Because they are printed on paper, we refer to them in literary terms-- comic book; graphic novel. In practice, the fact that comics stories convey scenes through images rather than through description, make them work on the reader more like film. Still, I wouldn't insist that comics be judged according to the criteria we use on film, since no one seems to agree on what those are either.

Literature vs. Film

People often repeat the fallacy that "film is a passive medium". The statement is usually elaborated like this: "When I read a story in a book, I have to use my imagination to conjure up what the characters look like, the sound of their voices, the appearance of their surroundings, the house, the landscape. When I see a movie, those things are all nailed down for me, so I don't feel as involved." What the person is describing are the most obvious aspects of a given story, that is, its physical properties. They are, in fact, the least interesting and least important components of a story. I do not read books in order to imagine the physical appearance of things.

This is a great book, but does it translate well as a movie?

This is a great book, but does it translate well as a movie?It's conundrums like this that has plagued the industry for decades.

Conversely, there are things which are typically spelled out in a book, but which must be imagined in a film. These are the intangibles, the important stuff; what are the characters thinking and feeling? Novelists have the advantage of being very explicit about the internal experience, and they indulge it, often to the detriment of the reader's power to infer. Good writers are the ones who maneuver around this pitfall. A book's ability to describe thoughts and feelings is a liability, not an advantage, if used to declaim its themes rather than evoke the desired consciousness in the reader.

Unfortunately, in practice, a great many mainstream filmmakers regard it as their job to inhibit interpretation by the viewer. No doubt, this is due to the increasing commercial pressures of the movie industry. Coming out of the theater after a thought-provoking film, I've heard viewers comment, "I was confused because I didn't know who I was supposed to be rooting for." Doesn't it occur to them that maybe that decision was being left up to them? That the exercise of our interpretive faculties is what makes our minds free? These people are usually the same ones who complain that movies don't let them use their imaginations.

In a review of Aeon Flux in the L.A. Times, the reviewer remarked that the director (me) wasn't doing his job in defining who in the story was good and who was bad, and thereby accused said director (me) of being "lazy". The presumptuousness of such an attitude would make me laugh, if only it weren't so prevalent.

A good film is one that requires the viewer to create, through an orchestration of impressions, the meaning of its events. It is, in the end, our ability to create meaning out of the raw experience of life that makes us human. It is the exercise of our faculty to discover meaning which is the purpose of art. The didactic imparting of moral or political messages is emphatically not the purpose of art-- that is what we call propaganda.

The inevitable challenge for anyone working in narrative film or comics is how to convey the internal states of the characters. Understanding this issue is the key to discerning visual versus literary storytelling. Resorting to the use of voice-over narration or thought balloons is a literary solution that undermines the power of images (the exception is in cases where narration is used ironically in counterpoint to what is being shown, e.g. A Clockwork Orange). For certain subjects, strict realism, where the mental realm of others is impenetrable, can be effective (e.g. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer). However, I would find it depressingly limiting as a filmmaker to be restricted to physical reality to express the world of ideas. Realism has the effect of granting primary status to the external, whereas in our experience, the internal is often the more important. The great filmmakers understand this trap -- that strict "realism" is, in fact, the least true interpretation of our experience of life; that a work springing from the imagination which adopts the guise of objective reality can only be a lie.

Void here.

Looking forward to your Peter Chung spotlight. I LOVE Peter Chung. =) (I have some website articles you might me interested in too; just ask for them if you'd like.)

(p.s. Stop your whining about the 'silent Void'. ;p You've got a DAMN good thing going here; you've got a great "mind" for art and animation analysis.)