Will Wright, creator of the 'Sims' brand of games, is one of those creative visionaries that has tried to push the boundaries with his kooky and off-the-wall ideas.

Will Wright, creator of the 'Sims' brand of games, is one of those creative visionaries that has tried to push the boundaries with his kooky and off-the-wall ideas.Example of Will's amazingly creative ideas over the years:

Who wants to be mayor of his or her own city?

Who wants to live the life of an ant colony? A farmer?

Who wants to control the evolution of a specie?

Who wants to control someone's life 24/7, as he or she eat, sleep, get a job, falls in love, etc??

Amazingly simple ideas that have eventually grown into the gaming world's most beloved, or better yet, biggest selling or franchises.

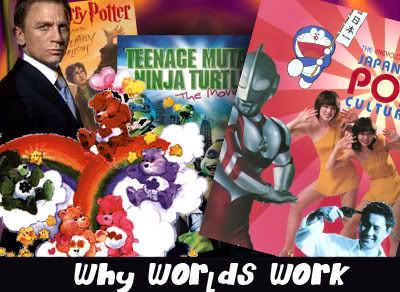

So now that you have an inkling to the 'brilliance' of this Will Wright character, I want to refer you my dear, indifferent Void™ to an article written on Gamespy.com by a certain 'Dave Kosak', during a presentation by Will Wright himself during the 2008's Game Developer's Conference. The article is entitled "Why Worlds Work", and it 'takes a step back in the universe of gaming to look at why some franchises take root in our brains'. I'll post it here, and see if I can inject my own idiotic ideas to Mr. Wright's brilliance.

What do Gilligan, Godzilla, and James Bond have in common? Not much at first blush. But these iconic characters have immortality in popular culture. Why? What makes one world or franchise appealing? What gives it "legs?"

The Essential Ingredients of a World

When does a product become a world? At some point franchises take on a life of their own. Wright showed a pyramid with the points labeled:

Story

Branding

Play

Branding

Play

This spectrum can fill up with products. For example, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles started as a comic book, a story product. Then it moved into collectables, or branded products. Suddenly the turtles became toys, games, a cartoon series, a movie... and the whole pyramid filled out.

The Care Bears took a similar journey from the most unusual of places: They started out as greeting card characters. Then they became a series of stuffed animals sold at greeting card stores, which before long turned into an animated kids' television show, a movie, and so on. It's not hard to find other examples that filled up the whole pyramid, including Star Wars, arguably one of the most popular worlds ever created.

Branding is a particularly interesting point in the pyramid that Wright focused on for a few moments. People who identify with a world start to use branded products to express their own identity. I thought here of my wife, who brings a Wonder Woman coffee mug to her straight-laced job every day. The mug shows Wonder Woman in her suit and tie, twirling around to reveal her costume, presumably to fly off and kick some ass. The idea of Wonder Woman took root in my wife's mind and she uses that mug as a form of self expression.

I personally didn't like Halo's Master Chief that much, but hey, the idea to play super space marine who spouts cheesy one liners and gets away with it is pretty cool in itself

I personally didn't like Halo's Master Chief that much, but hey, the idea to play super space marine who spouts cheesy one liners and gets away with it is pretty cool in itselfSo what makes a world sticky? Wright identified three things that help it to take root:

First, there are identifiable archetypes:

Characters whom we immediately understand at a deep level, whether it's the father-figure of Obi Wan Kenobi or the chilling mercilessness of Darth Vader.

Then there's exciting environments for the characters to interact in:

Imagine the snowy wastes of the planet Hoth or the mysterious intrigue of James Bond's cold-war Budapest.

Finally, there are cool actions that the characters in this world can do:

This is what Wright called the "verbs" of the world. James Bond has crazy gadgets. Harry Potter can use magic. Spider-man climbs and swings from buildings. Jedi Knights can use the Force... Even if the characters aren't super-heroic, they do things that people can fantasize about, creating stories in their heads.

Here's a world you probably haven't thought much about: Gilligan's Island. Wright pointed out that the seven castaways of the island are archetypes representing the seven deadly sins (Pride for the Professor, Greed for Thurston Howell III, Wrath for the Skipper...). Plop these archetypes in an exotic setting and suddenly everyone can start to relate to it in interesting ways. Personally, I can't count the number of times I've been asked the "Ginger or Mary-Ann?" question. (For the record, I always said Mary-Ann, but I was lying. And I married a redhead.)

My thoughts:

Cool. Seven deadly sins? I don't know a lot about Gilligan's Island though my dad loves it. Maybe he knows what Mr. Wright is talking about in the last part of the paragraph! About the show though... I did hear that the show ended with the kooky cast not getting rescued - but subsequently were in a bunch of made-for-TV movies... So you might ask - is that canon? Hardy-f**king har.

Gamespy:

Wright went back and emphasized his point about people putting themselves into the fantasy of the world, asking what-if questions. "What if Cylons attacked the Death Star?" "What house would I want to live in if I went to Hogwarts?"

This inspires people to interact with the universe, and eventually to play, to build their own version of the world. Wright's always been fascinated by the Lego world, where you can literally play and build things. He points out how appealing it was to combine the Lego and Star Wars worlds -- how blending together all of the archetypes and verbs created a whole new experience that literally brought out the best of both worlds.

This inspires people to interact with the universe, and eventually to play, to build their own version of the world. Wright's always been fascinated by the Lego world, where you can literally play and build things. He points out how appealing it was to combine the Lego and Star Wars worlds -- how blending together all of the archetypes and verbs created a whole new experience that literally brought out the best of both worlds.The James Bond franchise is in many ways the perfect world: to the tune of 14 books, 24 movies, and $4.5 billion dollars. It's loaded with iconic characters, from the suave James Bond to the sexy vixens to the over-the-top supervillains and their unusually talented henchmen. It's got exotic environments and more verbs than you can shake a laser-beam buzzsaw bomb-detonating wristwatch at. The world has blossomed to incorporate not just books and movies but games and merchandise. Bond has seeped into (or maybe out of) our collective subconscious.

But 24 movies is nothing! The most prolific film series ever clocks in at 28 feature-length films: Godzilla. Wright described vividly how he first encountered Godzilla on the family TV when he was just a kid and how he hid behind the couch for the entire movie. (I couldn't help but note that Wright lovingly incorporated a Godzilla-like monster in the original SimCity). Godzilla has his own star on the Hollywood walk of fame. And audience interaction? Wright showed images of Japanese fan clubs that to this day still prepare contingency plans -- using actual topographical and military data -- so that they're ready for a Godzilla attack.

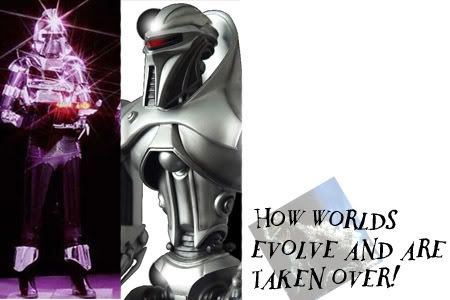

Franchises evolve over time. Godzilla started off as a city-devouring monster, but over the course of a dozen movies the filmmakers broadened his appeal to kids by making him cuter, friendlier -- sometimes the good guy. His eyes got bigger and his face rounder over time. By 1973 people saw the franchise as goofy entertainment for kids. After a decade hiatus, Godzilla was reborn -- as a scary monster once more -- in the 1984 remake.

Worlds change with the times. Battlestar Galactica was originally a goofy '70s space-opera with lots of lasers and exploding robots. The modern remake is darker, more believable, more morally gray: a better reflection of our confusing times. Wright pointed out that his own SimCity evolved as well: each successive game got more realistic and hardcore, until EA rebooted the franchise with SimCity Societies, a far more casual design.

That remake shook up a lot of fans who expected hardcore city simulation. Their reaction isn't surprising: "There's an amount of ownership in these worlds," Wright explained. Lost is the perfect example of a world that the community at large can embrace. Wright described it as "a giant puzzle game," with millions of fans trying to piece it together. Information is shown on the television program that people can freeze-frame and analyze on the net. In many ways, the fan involvement around Lost is as much a part of the world as the story itself.

That remake shook up a lot of fans who expected hardcore city simulation. Their reaction isn't surprising: "There's an amount of ownership in these worlds," Wright explained. Lost is the perfect example of a world that the community at large can embrace. Wright described it as "a giant puzzle game," with millions of fans trying to piece it together. Information is shown on the television program that people can freeze-frame and analyze on the net. In many ways, the fan involvement around Lost is as much a part of the world as the story itself.My thoughts:

Y'all didn't think I'd bring up fan entitlement? Well, being someone who came from a fandom as indifferent as Robotech, I have to agree with Mr. Wright here. Oh, and fan involvement sorta reminds me of my ol' favorite topic on this blog - Multi-layered Storytelling. Go on and read that! It's pretty cool if you keep an open mind.

What Makes a World Successful?

There was a time when Robotech's dynamic universe captivated me for months. The lack of any good merchandise over the years made me 'take measures into their own hands' - such is the allure of these pre-fabricated, fictional worlds

There was a time when Robotech's dynamic universe captivated me for months. The lack of any good merchandise over the years made me 'take measures into their own hands' - such is the allure of these pre-fabricated, fictional worldsThis interaction is key to what makes a world become more than a story, a comic book, a toy or a game. "Successful worlds are deconstructible," Wright theorizes. These iconic worlds take root inside your brain and, well after you finish the book or win the game or leave the movie theater, you find yourself asking: "What if...?" or "I wonder..."

What would it be like to swing from buildings like Spider-man? What would you do if you found out Darth Vader was your father? Could Captain Kirk's Enterprise take out the Battlestar Galactica? (Hold on while I stop writing to think about this one for a bit. At first blush I'm thinking no way, not with those vipers, but on the other hand -- it's Captain Kirk.)

Of course, games can be an essential part of any world, since they allow people to actually play out those fantasies.

Interestingly, Wright points out that this is a cyclical process. When you run across a good story, you can't help but deconstruct it in your head. Then you play around with it. From this play, you create new stories, and the process starts over. Story leads to deconstruction which leads to play which generates stories. Wright didn't say it, but it's clear to me that The Sims fits nicely into this feedback loop, allowing millions of people to play and create and share their stories, inspiring other people to make their own.

Cool worlds are at the heart of modern storytelling. The act of deconstructing a world allows us to apply the fiction to reality. Few of us can claim to have Darth Vader as our dad, but as Wright points out, many of us have had to deal with an overbearing parent. The war between the cylons and humans in "Battlestar Galactica" has eerie (and intentional) parallels to the post-9/11 world. And of course the storytelling that emerges from taking apart a world leads to a communal experience, as anyone who's read a "Lost" fan forum or attended a "Star Trek" convention can attest.

Cool worlds are at the heart of modern storytelling. The act of deconstructing a world allows us to apply the fiction to reality. Few of us can claim to have Darth Vader as our dad, but as Wright points out, many of us have had to deal with an overbearing parent. The war between the cylons and humans in "Battlestar Galactica" has eerie (and intentional) parallels to the post-9/11 world. And of course the storytelling that emerges from taking apart a world leads to a communal experience, as anyone who's read a "Lost" fan forum or attended a "Star Trek" convention can attest.My thoughts:

Aaah. Fictional worlds. Aren't they great? I hope you learned a lot from this, again, special thanks to Gamespy for such a great article.

You know what this article has forced me to do? Show another one of those wacky Star Wars. vs. Star Trek vs. whatever videos again. Oh well. Here you go. Remember: this is the product of people who dream up these fan what-ifs. Noooooooo. Thank you Will Wright!!!

0 comments